By Sophia Dramm

It’s a hot, bright summer day in Madison and you’re heading to Memorial Union Terrace to enjoy the weather. You’ve been planning this day-cation all week with your friends to relax after long, boring days at your summer jobs. On your to-do list is, of course, enjoy cold Babcock ice cream, snap pics in the sunburst chairs and take a dip in the lake. You’re looking most forward to swimming because the sun is beating down brutally, especially after the sweaty trek over.

You reach the Terrace and make your way to the pier, kicking off your shoes and throwing down your bag. Poised to cannon-ball in, you look down at the water. That’s when you see clumps of algae and suddenly, a jump in the crisp water is a lot less appealing than it was moments ago.

You can thank the spiny water flea for that.

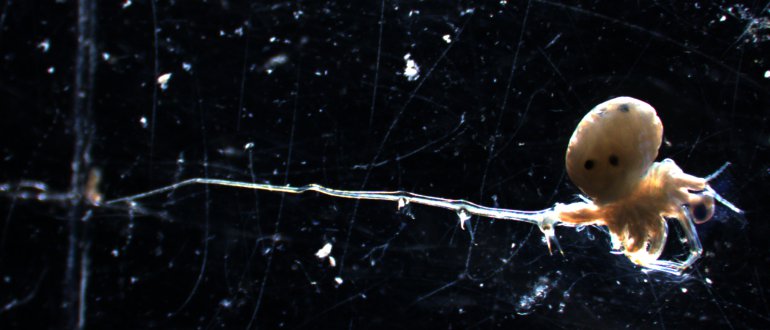

The spiny water flea is one of the invasive species currently lurking in Lakes Mendota and Monona’s waters. The small crustacean preys on Daphnia, a tiny organism known as the common water flea that eats a significant amount of algae which leads to clearer, more swim-able water. They’re “our ally in clean water,” according to Jake Vander Zanden, Director of the Center for Limnology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. With less Daphnia, a lot more algae stays in the water.

Invasive species are organisms that are not native to an area and cause harm to an ecosystem and beyond, according to the Dane County Office of Lakes & Watersheds. They are problematic because they don’t have predators so they reproduce quickly and out-compete native species, which can result in decreased diversity. The spiny water flea along with the zebra mussel, a clam-like organism that feeds on microorganisms by filtering water, are two of Madison’s waters’ most concerning invasive.

“Spinies and probably zebra mussels…are probably the two that we focus most of our attention on because they are so detrimental,” said Pete Jopke, Water Resources Planner for the Dane County Land and Water Resources Department. They’re detrimental because they disrupt aquatic ecosystems and impact water quality, as well as affect life on land.

For example, to regain the water quality that was lost due to spiny water fleas since 2009, it would cost about $100 million, according to Vander Zanden. This amount of was determined by calculating how much it would cost to change land-use practices like farming to reduce phosphorus production (another main cause of algae) and surveyed people in Dane County about how much would they be willing to pay for improvement of water quality, both of which totaled about $100 million.

“You can talk about the ecological impacts…but when you put it in economic terms, it feels a little more concrete,” said Vander Zanden.

Like water fleas, zebra mussels also contribute to algae problems. Their filter feeding is selective and blue-green algae, which is toxic to some aquatic life, is one of the things they don’t eat. In the summer 2017, Madison’s lakes saw historical blue-green algae blooms due to the presence of zebra mussels. Their feeding process also depletes the water’s nutrients for other fish to eat.

Effects like these brought by zebra mussels exemplify how the aquatic ecosystem is so interconnected.

“If you tweak the number of top predators in your system, it can trickle all the way down to the bottom of the food chain and change how much algae is there,” said Vander Zanden. Spiny water fleas particularly showed this, with their preying on Daphnia, in 2009 when the population boomed in Lake Mendota and water quality decreased greatly.

On-land influence

Because these species do not live on land and are seemingly far away from us, it’s often hard to see the impact they have on human life. But with the huge effects they have on ecosystems, it makes sense that those effects have impacts on us in some ways.

One obvious effect is that of increased algae production from spiny water fleas and zebra mussels, which can affect swimming and other water recreational activities.

Another effect of zebra mussels is how their filter feeding results in more clear water. For some people, this is a good thing.

“If you never go out on your lake but you just kind of look at it through your window or something like that, you might like the fact that zebra mussels are in your lake because your water’s really clear,” said Tim Campbell, Aquatic Invasive Species Outreach Specialist for the University of Wisconsin-Extension, University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute and Wisconsin DNR.

However, the clarity goes beyond pleasing window-watchers. With clearer water, more sun can stream through, affecting plants and fish behavior. This increases rooted plant growth, which gives more habitat for fish; fish also move to live in deeper and darker areas to avoid sunlight. These factors may impact fisheries and affect fishing. In addition, the sunlight fosters growth of blue-green algae – the bad stuff that is toxic to some fish and makes water less appealing to swim in.

“Through the right lens, there are some positive things about invasive species,” said Campbell. “But they really get that label [of invasive] because…there’s an overwhelming [amount of evidence] that impacts are negative, but sometimes there’s a few things that people like about them.”

Practicing prevention

Another impact of invasive species on humans is the efforts to prevent the spread of them. Because spread is based primarily on humans’ movement throughout areas, prevention is a public effort. For example, boaters are required to drain water from motors and wells, and clean biological material like weeds and mud off of boats before leaving a body of water.

“[The spread of invasive species is] basically a function of globalization,” said Paul Dearlove, Senior Director of Watershed Initiatives at Clean Lakes Alliance. Species can be brought by humans to an area on purpose, like if they want a specific animal in an area, or by accident, by species “hitchhiking” via transportation like boats.

“Humans move around invasive species and human behavior can change, and so therefore invasion is preventable.” Campbell said.

Other efforts for preventing spread include funding from the Wisconsin DNR for education and outreach work. The DNR and the Wisconsin Sea Grant fund research work to better understand invasives. The Clean Boats, Clean Waters program trains volunteers and paid staff to inspect boats and talk to boaters about spread prevention. The Citizen Lake Monitoring Network program teaches citizens how to monitor lakes for invasives.

Stopping the spread of invasive species is critical because of the major – and usually negative – changes to waters that aquatic invasives can bring. The distinctiveness of Wisconsin’s lakes and ecosystems is important to preserve too. For example, sturgeon spearing in Lake Winnebago is “uniquely Wisconsin,” said Campbell. (“It should probably belong in the same category as being a Packers fan.”) A few years ago, round gobies, an invasive fish species known as a lake sturgeon egg predator, was found outside of Lake Winnebago.

“It’s hard to say what would happen to lake sturgeons if round gobies got into Lake Winnebago… I think that experience [of sturgeon fishing] is just so valuable to Wisconsin,” said Campbell. “I hear stories of people going up to hang out at the family lake house or something, and they have a story or experience they like to tell, and invasive species could change that experience.”