By Will Kenneally

There are two cities in the country that are built around isthmuses: the larger being Seattle, and the smaller being the familiar setting of Madison, Wisconsin. In Madison especially, the geography of the isthmus defines the culture of the city–shaping neighborhoods and even lending its name to one of the city’s weekly periodicals The Isthmus.

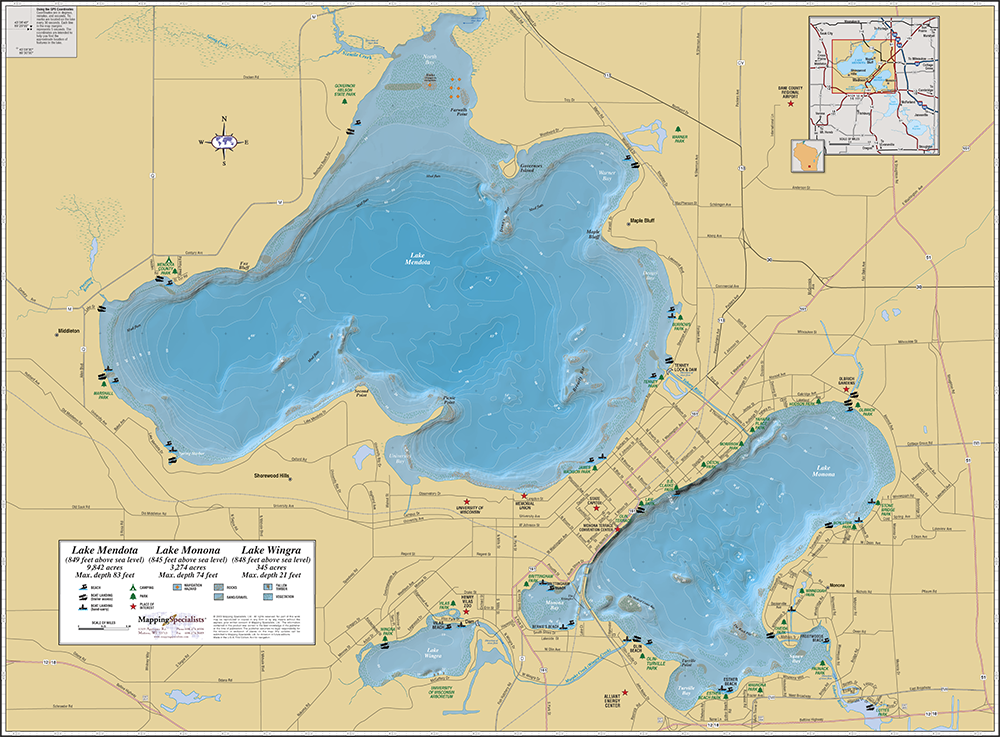

The two lakes of Mendota and Monona define the shape and culture of Madison, but they play crucial roles in the surrounding communities as well. Villages like the enclaves of Maple Bluff and Shorewood Hills are nestled up against Lake Mendota, while the area’s second lake lends its name to the city of Monona.

Though the communities along Lake Mendota and Lake Monona exemplify their own cultures and face their own challenges, there is a strong sense of camaraderie among the communities when it comes to their relationships with the lakes.

“We all work together to keep the water clean and and that’s very, very important,” said Gurdip Brar.

He would know; as the mayor of Middleton, Brar works with Madison and other communities in Dane County to maintain the long-term quality of the area lakes. Not only is this work for his constituents, but it is of personal importance for Brar as well.

“My wife actually likes [paddle] boarding, and when there is the algae and all that stuff it can be pretty toxic,” Brar said.

The mayor spoke at the recent unveiling of a new sewage pump located along the bank of Lake Mendota. The pump renovation was a project of the Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District, an inter-governmental agency that coordinates sewage resources across municipalities in the Madison area, but also promotes the health of the lakes.

The newly renovated facility gives credence to Middleton’s monicker of “the good neighbor city.” While the pump’s primary purpose is to connect local sewer lines to the regional sewer infrastructure, the facility touts bioretention basins to stave off runoff and invasive species boat wash hydrants, according to its website.

“This project is more than just pumping wastewater it’s about how we be a good neighbor in the community,” said Michael Mucha, chief engineer of the project and President of the MMSD. “We’re using the public’s resources to make this happen.”

This spirit of collaboration extends further than just renovation of old facilities. The MMSD spearheads the Yahara Watershed Improvement Network (Yahara WINS) to broadly study how to keep the lakes in Dane County clean.

“Yahara WINS is an example of an innovative and collaborative project aimed at improving water quality,” MMSD Communications Manager Jennifer Sereno wrote in an email. “These partnerships allow for allocation of pooled resources across the watershed with results driven by practices that are often much less expensive…than individual actions.”

The collaborative work of Yahara WINS brings in communities that do not even border the lake. A significant portion of the grant money the program allocates goes to the UW-Extension office of Dane County to help farmers plant cover crops, according to a 2016 annual report. The organization partners with municipalities such as Windsor or Bloomington Grove, which represent rural, agricultural communities that still have a stake in the health of the lake system.

Mucha explained that as the growth of the metropolitan area is concentrated away from Madison, it is increasingly important to engage these communities and reaffirm the important role they play as part of the watershed.

Sereno echoed a similar sentiment, writing that “partnerships are necessary to implement solutions ranging from aerial seeding of cover crops and advanced manure injection technology to improved urban stormwater management and leaf collection practices.”

Understanding these best environmental practices is common across the lakes. A short trip east lands one in the city of Monona, which plays host to the Aldo Leopold Nature Center. The center charges itself with educating the next generation on the importance of the environment in the hopes that they embrace the notion of environmental stewardship.

“If we teach children to love the land, they will then be able to make decisions on how to care for the land,” Trish Stevenson, ALNC board member and granddaughter of Aldo Leopold, said in a video for the center.

The center hosts children from Monona and the surrounding communities for summer camps and classes.

Though the ALNC’s goal is to educate children on best environmental practices, in Middleton the effort is ongoing to teach the current generation what they can do to help maintain the health of the lakes.

Phosphorus, a major contributor to toxic algae blooms in the lakes, can be washed off of fallen leaves in autumn. Mayor Brar explains his frustration with residents who are careless when it comes time to rake their yards.

“Rather than keeping it on the boulevard they put it into the gutter,” Brar said. “And then where do you think it’s going to go–it’s going to go into the storm drain and that’s simply unacceptable.”

Brar said that an initial pilot program to educate residents was rather successful in encouraging people to change their behaviour.

“It’s a great tool when people are educated. Most people will be responsible and they will do [what is best],” Brar said.

Brar hopes that the example his city sets can be a model for the broader community and the state. The sewage pump, of the unveiling event at which Brar spoke, is the first piece of infrastructure in Wisconsin to be awarded the Envision Gold Award for sustainability.

“Middleton is a leader in this water resource management. It has always been and we plan to stay that way,” the mayor said.

Brar says he is always looking for the next innovation to keep the lakes clean.

“Could we be doing better? Absolutely. But whenever we find something which we could do, we do it,” Brar said. “It’s not that we sit on it.”

“It’s always a question of making choices–how do you prioritize,” Brar said. “We are fortunate in the great lakes [and] in Wisconsin…you don’t want water to become the problem.”